Issue 10

Towards a more conscious autonomous future: Part Two

This is the second part of a piece on cities and autonomous vehicles. Find Part One here.

Autonomous Vehicles

Into the void of congestion and urbanism woes steps autonomous vehicles—always, it seems, one-to-two years away. For proponents, AVs represent the ideal one-and-done solution. Because they don’t fall prey to human fealty, we’re told, AVs will eliminate congestion from merging by “zippering” perfectly. They’ll eliminate human-caused phenomena like rubbernecking and all manner of other accidents. So long, Russian dash cam compilations.

The other supposed form of congestion easing claimed by AV proponents is shared ownership. Because the vehicles can drive themselves, individual car ownership will be relegated to the past, and every trip we take will be like an ultra low cost Uber. This more efficient resource utilization will supposedly leave fewer vehicles on the road.

Most importantly, AVs won’t require us to change anything about the way we currently live our lives and organize our cities—except, proponents tell us, the unmitigated benefits of eliminating wasteful on-street parking and parking lots. AVs can be parked on the edges of cities or in super compact garages—allowing land and indeed entire floors of buildings currently devoted to parking to be put to more productive use. Sounds great.

But like most techno-utopian visions of the future, this one deserves scrutiny.

To be clear, autonomous vehicles will provide unquestionable benefits—the freeing up of time for travelers to be productive, to watch content, play games, or video chat will be huge. The transformation in time use will almost certainly pave the way for new and unexpected uses for drivetime. AVs will change the housing market, freeing up space previously used for parking lots for development. Because commutes will be less painful, they’ll also let people settle further out into the suburbs, where land and housing is cheaper.

With time, AVs are also certain to eliminate traffic fatalities—a benefit the impact of which cannot be overstated.

But as for the afflictions of urban traffic?

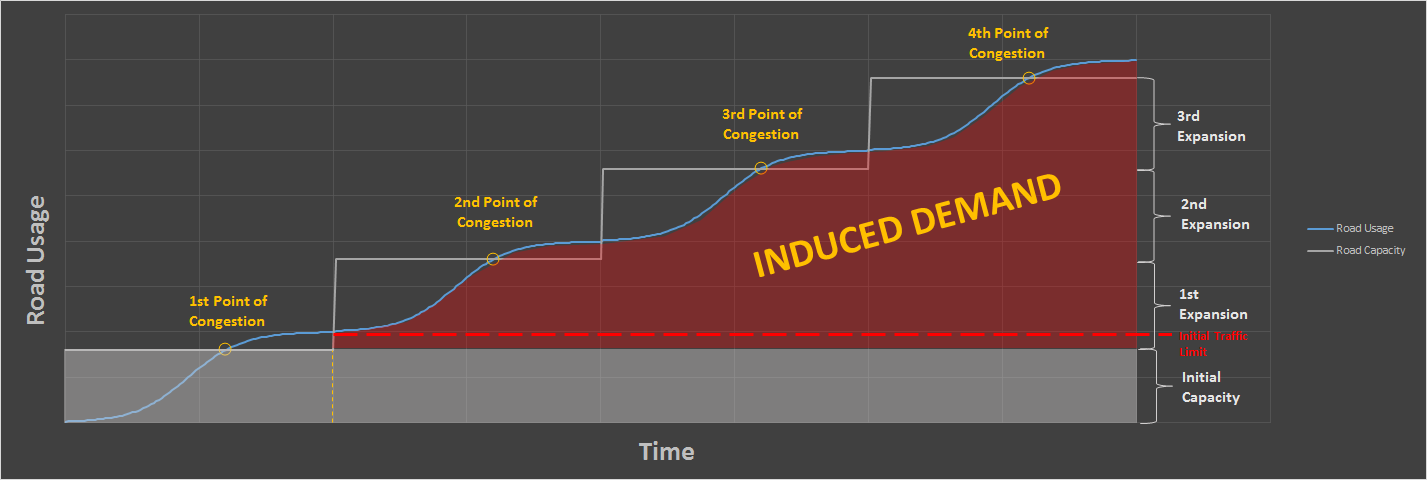

The claims are dubious to say the least. The primary reason why is what, in transportation planning, is referred to as induced demand. Induced demand says that when adding additional capacity to satisfy demand (for instance, adding lanes to clogged highways), the result is that additional demand is generated. With added capacity, now drivers start to recognize this route as the fastest way to their destination, soon word spreads, and before you know it: traffic moves slower than it did before the additional capacity.

The phenomenon has been recorded again and again—it’s what makes highway expansion projects self-defeating.

When autonomous vehicles see widespread adoption (and correspondingly low prices, likely much lower than Ubers or taxis today), there will be no more convenient form of transportation in existence. This is exactly the problem—the demand will grow accordingly as users opt to travel by AV instead biking, walking, or riding the subway.

This is a problem because of math: there simply will not be enough space on urban roads to meet demand.

The Upshot

We’ll get into what all this means in the next issue. Stay tuned.

This is a freeform daily newsletter about the transportation industry: Planes, Trains, and Automobiles. I take shallow dives into topics that I think are interesting, including write ups of startups in the space, historical explorations, market analyses, company and personal profiles, interviews with industry players, and occasional personal essays.

Thanks for reading—and please let me know if you have any feedback or if there is anything you would like to see me cover.

Ride well,

DS